More Information

Submitted: December 11, 2023 | Approved: December 26, 2023 | Published: December 27, 2023

How to cite this article: Laviolette-Brassard M, Tu LM. Case – Late Presentation of Invasive Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Arch Case Rep. 2023; 7: 080-082.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001084

Copyright License: © 2023 Laviolette Brassard M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Penile cancer; Squamous cell carcinoma; Diagnosis, Metastatic; Screening; Stigma; Quality of life; Risk factors

Case – Late Presentation of Invasive Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Maximilien Laviolette-Brassard* and Le Mai Tu

Urology department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS), Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

*Address for Correspondence: Maximilien Laviolette-Brassard, Urology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS), Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, Email: maximilien.laviolette-brassard usherbrooke.ca

Penile cancer, a rare but highly morbid disease, primarily manifests as squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) originating from the squamous cells of the glandular and preputial skin. Late-stage diagnosis is common due to social stigma, psychological barriers, and nonspecific initial symptoms, resulting in poor overall survival rates, especially in metastatic cases. This case report illustrates a 38-year-old man with advanced metastatic PSCC, showcasing severe systemic manifestations and delayed presentation of the disease. Despite aggressive treatment options, the patient opted for palliative care, succumbing to the disease months after his diagnosis.

Risk factors for PSCC include HPV infection, phimosis, chronic inflammation, and lifestyle factors, with higher prevalence in regions of low socioeconomic status. The psychological and sexual burden of penile cancer is significant, impacting patients’ well-being, mental health, and quality of life.

In conclusion, efforts to reduce the stigma associated with penile cancer are crucial to prompt early diagnosis and treatment initiation. Encouraging seeking medical attention for symptoms can enhance the chances of recovery and minimize the need for invasive treatments. Addressing the psychosocial impact of the disease is imperative for holistic patient care.

Penile cancer is a disease with high morbidity and mortality. It is a rare illness for which only 26,000 cases are estimated globally per year, accounting for less than 1% of newly diagnosed cancers in men [1]. Most penile cancers (95%) arise from the squamous cells of the glandular and preputial skin, classified as squamous cell carcinoma (PSCCs) [2]. They can further be classified based on their histological feature as follows: usual type (59% of cases), papillary (15%), basaloid (10%), warty (condylomatous, 10%), verrucous (3%), and sarcomatoid (3%) [3]. More recently, HPV expression has been used to classify penile cancers into morphologically and molecularly distinct subtypes, including HPV-related and non-HPV-related, by the classification system adopted by the World Health Organization [4].

The majority of men (up to 40%) are diagnosed with localized penile cancer, which has a 5-year overall survival of ~ 90%; however, once the tumour has metastasized, the prognosis worsens dramatically [5]. Due to poor public awareness and feelings of shame, most penile cancers have a delayed presentation and are clinically apparent [6].

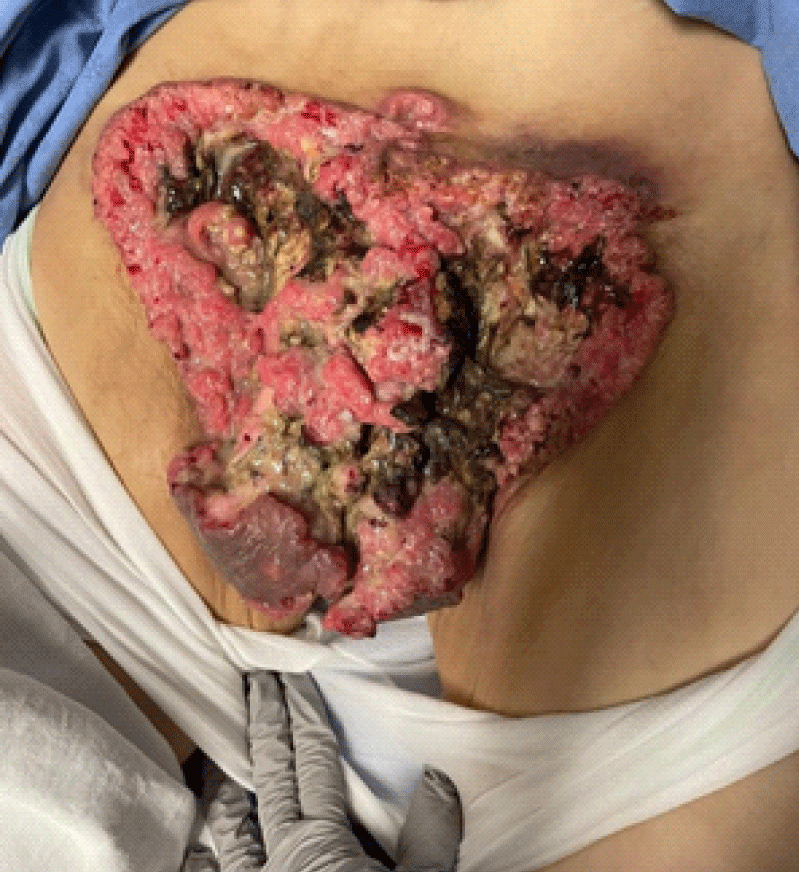

A 38-year-old man with no known medical history presented to the emergency department of our centre with intense fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss. The patient was afebrile, and his vitals were within normal limits. Blood work revealed increased inflammatory markers (CRP and WBC), acute kidney injury, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, metabolic acidosis, elevated lactate, and severe anemia (necessitating blood transfusions). Upon physical examination, a large purulent and necrotic abdominal-pelvic lesion was discovered. The patient mentioned that the lesion started on the tip of his penis approximately two years ago. At that time, the patient was embarrassed to seek medical attention and had no systemic symptoms. A non-contrast abdominal-pelvic CT scan revealed bilateral inguinal adenopathy and prominent internal and external iliac lymph nodes. CT thorax was negative for pulmonary metastases. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for severe electrolyte disturbances and management of the infected cutaneous lesions.

Figure 1: Initial presentation at time of diagnosis in the emergency department.

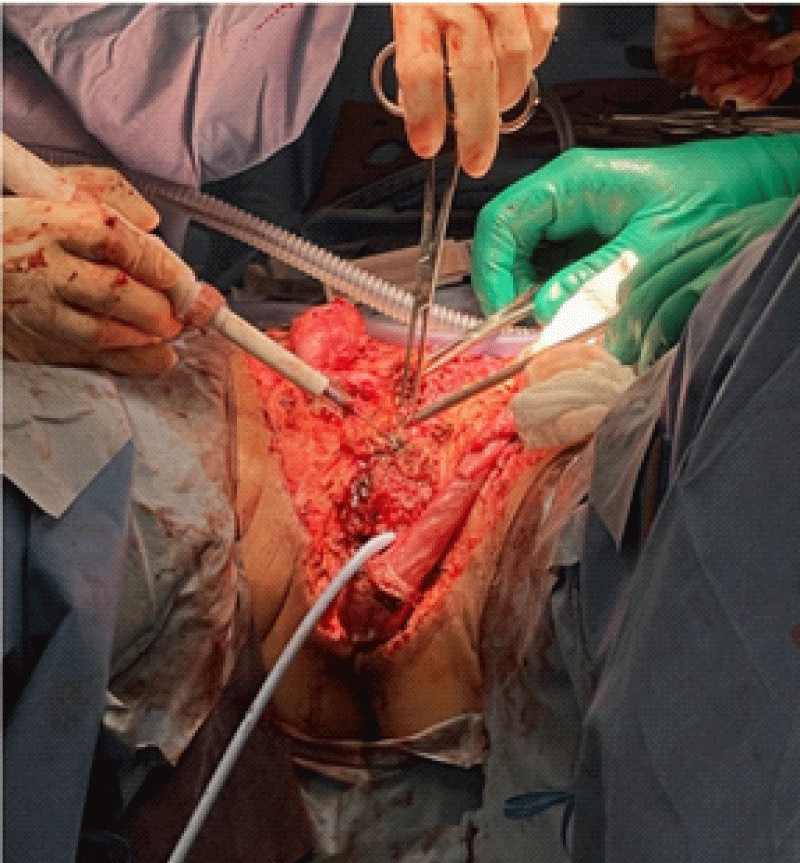

Figure 2: Surgical exploration and extensive debridement.

The day after his admission, when his electrolytes and general condition were optimal, he underwent an extensive surgical excision of the abdominal pelvic necrotic and infected lesion. The inguinal canals, testis, and the edges of the wound were debrided. Multiple intraoperative cultures and specimens were collected. The urethra was found during the surgery, and a flexible cystoscopy was performed. There was no evidence of intravesical invasion of the lesion. An open-ended 16 Fr Foley catheter was inserted with a guide wire, and the bladder was continuously drained postoperatively. Extensive washing with normal saline and proper hemostasis was performed. Larges compresses soaked in betadine, and a sizeable abdominal pad were applied. The specimens and cultures were sent to the pathology and microbiology laboratories for analysis. The intraoperative cultures were positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus Group B, Peptostreptococcus Sp, Clostridium innocuum, and Campylobacter ureolyticus. The pathology report was consistent with metastatic invasive keratinizing penile squamous cell carcinoma, HPV-independent type.

On postoperative day 3, the patient had a PET scan that suggested a plurimetastatic disease. Imaging showed left and right inguinal, left external iliac, and aortocaval lymph node involvement, representing stage IV disease.

The oncologist offered the patient chemotherapy with Taxol, Ifosfamide, and Cisplatin (TIP). Given the patient’s clinical situation, he and his wife decided not to go ahead with systemic treatment and to implement a purely palliative treatment. Two months later, he was admitted to a Palliative Care Centre for a decrease in his general condition and severe pain. Unfortunately, he passed away 24 hours after his admission.

Unfortunately, delays in the diagnosis of more than six months are not uncommon regarding patients with penile cancer [7]. The main reasons include social stigma and psychological consequences in describing the problem to their doctor or partner, insidious and nonspecific initial symptoms, concomitant phimosis masking the malignant lesion, and a lack of awareness of the condition [8]. Several risk factors for developing PSCC have been reported: infection with HPV, the presence of phimosis, chronic inflammation (e.g., lichen sclerosus), and lifestyle factors (tobacco use, obesity, poor penile hygiene). Furthermore, it has been shown that PSCC is more common in regions with low socioeconomic status and education, as risk factors such as lack of circumcision, poor hygiene, and HPV infection tend to be more prevalent in these locations [9].

No dedicated programme for PSCC currently exists. In countries with screening programmes for other cancers, the low prevalence of penile cancer means that it does not meet the criteria for screening programmes. However, patients tend to present at a late onset, and the disease has already progressed. Overall survival for metastatic disease is ~ 80% for unilateral inguinal lymph node involvement of ≤ 2 nodes (stage N1 or limited N2), 10% - 20% for bilateral or pelvic lymph node involvement (stage N2 or N3), and < 10% in the case of extranodal extension [10].

Penile cancer can be a devastating disease with a considerable effect on the quality of life [11]. However, the literature on this aspect is limited and consists mainly of focus group investigations and semi-structured interviews-based qualitative research in small cohorts of patients [11]. Patients suffer from mental stress originating from their diagnosis, outlook on their prognosis, and ravaging treatment modalities [12]. The overall effects of penile cancer and its treatment negatively affect well-being, mental health, avoidance behaviour, and post-traumatic stress disorder [13].

PSCC is a rare disease with high psychological and sexual burden. (Audenet & Sfakianos, 2017) [14] Morbidity and mortality increase tremendously with the invasion of the disease and lymph node spreading. The stigma and shame associated with this condition negatively impact the diagnosis and often delay patients seeking help for their symptoms. The prevalence of PSCC has been shown to be higher in regions with low socioeconomic status and education. It is imperative to reduce the stigma associated with penile cancer and encourage men to seek medical attention when they experience symptoms. Early detection and treatment of this disease can improve the chance of recovery and reduce the need for extensive treatments.

- Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017 Nov 30;41:e117. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2017.117. PMID: 31384255; PMCID: PMC6645409.

- Thomas A, Necchi A, Muneer A, Tobias-Machado M, Tran ATH, Van Rompuy AS, Spiess PE, Albersen M. Penile cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb 11;7(1):11. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00246-5. PMID: 33574340.

- Cubilla AL, Reuter V, Velazquez E, Piris A, Saito S, Young RH. Histologic classification of penile carcinoma and its relation to outcome in 61 patients with primary resection. Int J Surg Pathol. 2001 Apr;9(2):111-20. doi: 10.1177/106689690100900204. PMID: 11484498.

- Cubilla, A. L., Velazquez, E. F., Amin, M. B., Epstein, J., Berney, D. M., Corbishley, C. M., & Panel, M. of the I. P. T. (2018). The World Health Organisation 2016 classification of penile carcinomas: A review and update from the International Society of Urological Pathology expert-driven recommendations. Histopathology, 72(6), 893–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13429

- Djajadiningrat RS, Graafland NM, van Werkhoven E, Meinhardt W, Bex A, van der Poel HG, van Boven HH, Valdés Olmos RA, Horenblas S. Contemporary management of regional nodes in penile cancer-improvement of survival? J Urol. 2014 Jan;191(1):68-73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.088. Epub 2013 Aug 2. PMID: 23917166.

- Lucky MA, Rogers B, Parr NJ. Referrals into a dedicated British penile cancer centre and sources of possible delay. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Dec;85(7):527-30. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036061. Epub 2009 Jul 6. PMID: 19584061.

- Stecca CE, Alt M, Jiang DM, Chung P, Crook JM, Kulkarni GS, Sridhar SS. Recent Advances in the Management of Penile Cancer: A Contemporary Review of the Literature. Oncol Ther. 2021 Jun;9(1):21-39. doi: 10.1007/s40487-020-00135-z. Epub 2021 Jan 16. PMID: 33454930; PMCID: PMC8140030.

- Skeppner E, Andersson SO, Johansson JE, Windahl T. Initial symptoms and delay in patients with penile carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2012 Oct;46(5):319-25. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2012.677473. Epub 2012 Jul 2. PMID: 22989150.

- Vieira CB, Feitoza L, Pinho J, Teixeira-Júnior A, Lages J, Calixto J, Coelho R, Nogueira L, Cunha I, Soares F, Silva GEB. Profile of patients with penile cancer in the region with the highest worldwide incidence. Sci Rep. 2020 Feb 19;10(1):2965. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59831-5. PMID: 32076037; PMCID: PMC7031540.

- Pagliaro LC, Crook J. Multimodality therapy in penile cancer: when and which treatments? World J Urol. 2009 Apr;27(2):221-5. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0310-z. Epub 2008 Aug 6. PMID: 18682961; PMCID: PMC4164341.

- Dräger DL, Milerski S, Sievert KD, Hakenberg OW. Psychosoziale Auswirkungen bei Patienten mit Peniskarzinom : Ein systematischer Überblick [Psychosocial effects in patients with penile cancer : A systematic review]. Urologe A. 2018 Apr;57(4):444-452. German. doi: 10.1007/s00120-018-0603-9. PMID: 29476193.

- Dräger DL, Protzel C, Hakenberg OW. Identifying Psychosocial Distress and Stressors Using Distress-screening Instruments in Patients With Localized and Advanced Penile Cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017 Oct;15(5):605-609. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.04.010. Epub 2017 Apr 21. PMID: 28499559.

- Maddineni SB, Lau MM, Sangar VK. Identifying the needs of penile cancer sufferers: a systematic review of the quality of life, psychosexual and psychosocial literature in penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2009 Aug 8;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-9-8. PMID: 19664235; PMCID: PMC2731105.

- Audenet F, Sfakianos JP. Psychosocial impact of penile carcinoma. Transl Androl Urol. 2017 Oct;6(5):874-878. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.07.24. PMID: 29184785; PMCID: PMC5673805.