More Information

Submitted: April 03, 2025 | Approved: April 21, 2025 | Published: April 22, 2025

How to cite this article: Elimam AMA, Babbiker IS, Ahmed ES, Omar AI. Successful Management of Co-twin Demise till Term, Case Report. Arch Case Rep. 2025; 9(4): 158-160. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.acr.1001138

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001138

Copyright license: © 2025 Elimam AMA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Twin pregnancy; Co-twin demise; Chorionicit

Successful Management of Co-twin Demise till Term, Case Report

Ali Mohammed Ali Elimam1*, Isam Mohamed Babbiker2, Elfayad Said Ahmed3 and Abdalmuein Ibrahim Omar4

1Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Al Neelain University, Sudan

2Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, University of Sennar, Sudan

3Senior Consultant, Anesthesiologist & Pain Management Physician, Military Hospital, Sudan

4Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Shendi University, Sudan

*Address for Correspondence: Ali Mohammed Ali Elimam, Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Al Neelain University, Sudan, Email: [email protected]

Single twin demise is a rare condition associated with serious complications to the surviving twin. It leads to increased rate of fetal loss, neurological damage, prematurity, maternal psychological trauma, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Outcome depends mainly on gestational age and chorionicity.

Conservative management is advised in a fetal medicine unit with close maternal and fetal surveillance. We report a case of successful conservative management for single twin demise at 30 weeks, till term without complications.

Twin pregnancies are more prevalent among individuals of African descent, the incidence is1:80 this is increased in relation to ovulation induction. Twin pregnancy is considered high-risk pregnancy with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Co twin demise is rare, for which risk factors include pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, Intra-uterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome (TTS), congenital anomalies, Velamentous cord insertion, and true knot.

Maternal and fetal complications are more common if twin demise occurs in the second or third trimester. Complications include: preterm-labor, Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC), fetal neurological damage, and renal- cortical necrosis.

Single Intrauterine Death (SIUD) represents significant risk for surviving twin with six-fold increase in cerebral palsy for monochorionic twins. The timing of death of co-twin and the fetal order at time of death have an impact on the outcome for the survivor. This neurological injury risk is lower in dichorionic pregnancies, but risk for prematurity remains high, especially if the dead twin is the leading [1].

In fetal demise there is both medical and psychological stress to both parents and attending obstetrician, this condition is also highly associated with medical complications [2]. The psychological trauma for parents is not well addressed for many health care providers and so is the stress and anxiety on care providers.

The absence of large-scale studies leads to difficulty in advising parents on the prognosis and treatment option [2]. The agreed treatment approach is conservative as no benefit from urgent delivery with risk of prematurity.

32-year-old lady, P2, VD with negative past medical history and no family history of twin pregnancy nor ovulation induction. Came from remote area with fever, shortness of breath, cough, and reduced fetal movement. She had amenorrhea for seven months. The patient was admitted and received treatment for severe pneumonia, other possibilities excluded by Multidisciplinary team.

On examination

She had restlessness, not pale or jaundiced, BP120/70, Fundal level 34 weeks, no lower limbs oedema. Investigations: Complete Blood Count (CBC) Hb10 g/dl, Leukocytosis with normal platelets, no malaria and negative for hepatitis screening, mid-stream urine analysis clear.

Ultrasound scan

Showed twin pregnancy, diamniotic dichorionic with negative cardiac activity in one of them, the second twin is viable 30 weeks breech presentation (leading twin), normal liquor volume, no features of fetal hydrops or other abnormalities. The dead twin measurement was lower with reduced liquor volume.

The patient was counseled about the findings and supported, received iron supplements and corticosteroids (to enhance lung maturity) and planned for fetal and maternal surveillance by serial ultrasound scan with Doppler test, Cardiac Tocography (CTG), CBC and coagulation profile. Patient agreed with conservative management.

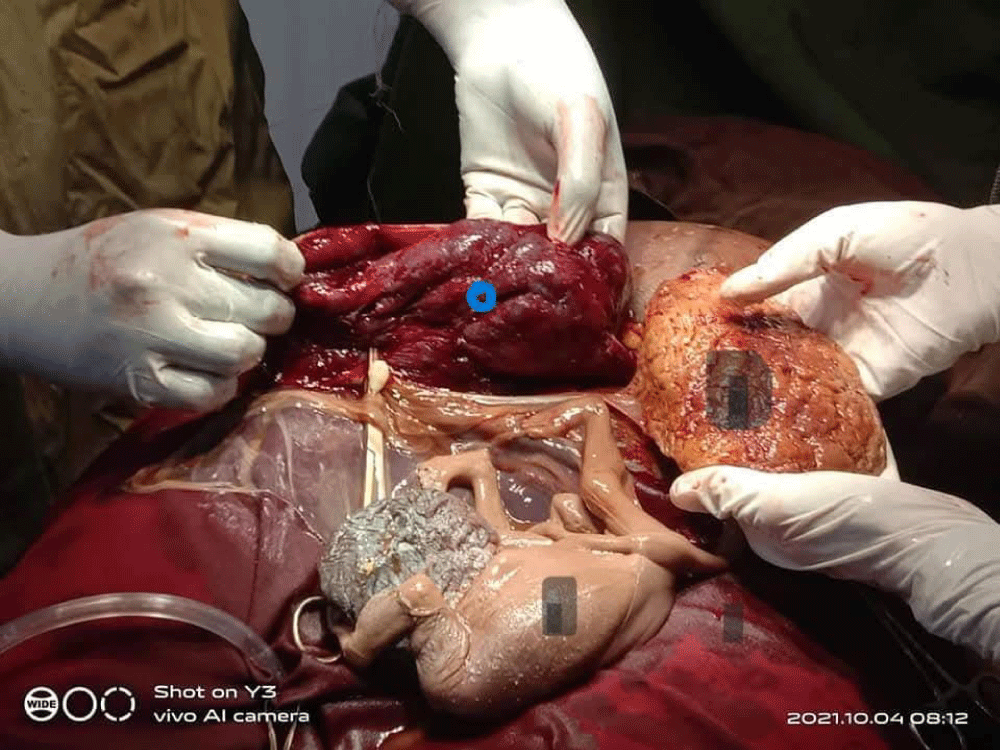

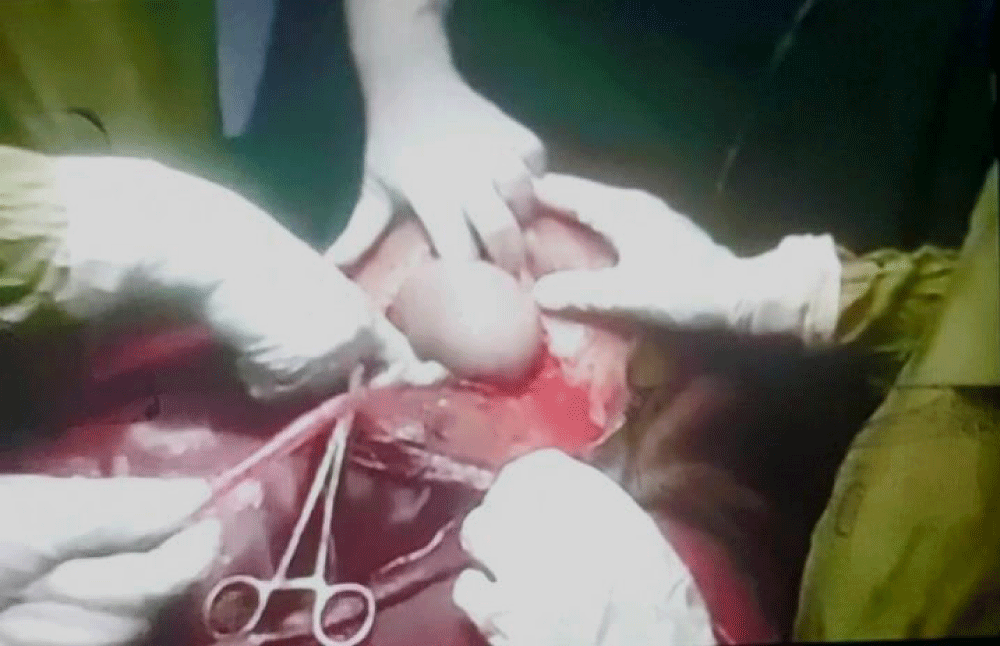

The patient was followed up until 37 weeks and delivered by elective caesarean section (persistent breech), under spinal anesthesia administered by a consultant anesthesiologist. The procedure was uncomplicated. This shown in Picture 1: Macerated co twin and its placenta, (Picture 2) the leading healthy twin. The baby remained clinically stable until discharge, evaluated by pediatrician and planned for further follow-up for future expected complications (Picture 3).

Picture 1: Macerated co twin and it's placenta (black mark), Placenta of the surviving twin (blue mark).

Picture 2: The surviving twin.

Picture 3: A macerated twin within the amniotic sac after delivery of the surviving twin.

Single fetal demise is serious condition with both psychological and medical complications that require multidisciplinary team in tertiary center. Although the management of single fetal demise should be individualized, there is general agreement that conservative management with maternal and fetal monitoring is agreed by majority of clinicians.

Single fetal demise is a serious concern in monochorionic twins because of the placental vascular anastomoses. The fetal death of one twin in a monochorionic pregnancy can cause acute hypotension, anemia, and ischemia in the fetal co-twin due to exsanguination into the deceased twin’s low-pressure vascular system, resulting in morbidity or death of the co-twin. In a dichorionic pregnancy, this sequence is not a concern since there are no placental vascular anastomoses; however, death of one twin may reflect an adverse intrauterine environment that could also place the co-twin at risk for morbidity or mortality.

Penelope et al found that; if a demised twin was present, delivery occurred earlier and resulted in more neonatal morbidity for the surviving twin [3]. This aligns with the clinical approach taken in our case.

One study found that in monochorionic twins with single twin demise, co-twin prognosis if death occurred before 28 weeks of gestation, has higher rate of co-twin intrauterine and neonatal deaths. The death of the second twin is attributed to vascular connections between the twins resulting in acute hypotension, anemia and embolus, this condition is rare in dichorionic diamniotic twins. Neonatal death was more likely in the presence of fetal growth restriction or preterm birth. And in monochorionic co-twins there is 20% of neonate with abnormal antenatal brain imaging [4].

The causes of fetal death vary and include twin–twin transfusion, placental insufficiency, IUGR related to preeclampsia, velamentous insertion of the cord, cord stricture, cord around the neck, and congenital abnormalities [5]. A specific cause may not always be identified, but even if tracing the cause is important.

Fetal loss in a monochorionic twin pregnancy has great emotional effect and leaves the mother psychologically vulnerable. The mothers are vulnerable regardless of presence of living children or survival of single twin [6]. This is also seen in dichorionic twin and singleton pregnancies, a fact that must be appropriately addressed and managed.

Conservative management of co-twin demise is best conducted in a fetal medicine unit and the timing of delivery should be individualized.

Gestational age and chorionicity are determinant factors for fetal outcome.

Close surveillance of both mother and fetus is essential to prevent complications.

Ongoing pediatric follow-up of the surviving twin is strongly recommended.

Declarations

Acknowledgement: Authors acknowledged the patient for using the data in this case report.

Ethical consideration: Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

Data availability: All relevant data are included within this manuscript.

Authors contribution: All authors have contributed on data interpretation and writing.

- Healy EF, Khalil A. Single intrauterine death in twin pregnancy: Evidenced-based counselling and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;84:205-217. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.08.009

- Stefanescu BI, Adam AM, Constantin GB, Trus C. Single Fetal Demise in Twin Pregnancy-A Great Concern but Still a Favorable Outcome. Diseases. 2021;9(2):33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases9020033

- Ward PL, Reidy KL, Palma-Dias R, Doyle LW, Umstad MP. Single intrauterine death in twin: the importance of fetal order. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2018;21(6):556-562. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2018.57

- Mackie FL, Rigby A, Morris RK, Kilby MD. Prognosis of the co-twin following spontaneous single intrauterine fetal death in twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2019;126(5):569-578. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15530

- Woo HH, Sin SY, Tang LC. Single fetal death in twin pregnancies: review of the maternal and neonatal outcomes and management. Hong Kong Med J. 2000;6(3):293-300. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11025849/

- Druguet M, Nuño L, Rodó C, Arévalo S, Carreras E, Gómez-Benito J. Emotional Effect of the Loss of One or Both Fetuses in a Monochorionic Twin Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47(2):137-145. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2018.01.004